LITTLETON — Reconstruction continues at the Arapahoe and I-25 interchange. To expedite work and maintain public safety, Yosemite Street will be closed in both directions for several weeks beginning April 28. The work will be completed in two phases, each lasting approximately 10 days. The first phase will be in effect April 28 to early May and will close Yosemite Street from Xanthia Street to Arapahoe Road (south of Arapahoe Road). The second phase will begin in early May. Yosemite Street from Arapahoe Road to Yosemite Circle (north of Arapahoe Road) will be closed during this phase. Business access will be maintained during both phases. Full closures enable the work to be done much more quickly than if using overnight closures. The closures also avoid the need to continually shift traffic and change conditions for drivers to navigate. These closures will allow for crews to shift Yosemite Street traffic to the west so utility relocations, wall work, permanent sidewalk and curb and gutter construction can be completed on the east side of Yosemite Street. Please drive slow, avoid distractions and watch for signage throughout the construction area. Pedestrians should watch for signage and flaggers and should never walk through the construction site. When possible, alternate routes are advised. Major reconstruction began May 2016 and consists of replacing the I-25 bridge over Arapahoe Road and other interchange improvements designed to reduce congestion and improve traffic operations and safety. I-25 lanes have been shifted to their final alignment. The remaining major work will now shift to Arapahoe Road and intersecting roadways. All work is weather dependent and subject to change. Work is expected to be mostly complete by summer 2018. Detour maps and more information are available at the project website https://www.codot.gov/projects/I25- Arapahoe or by calling the project hotline 720-580-2525.

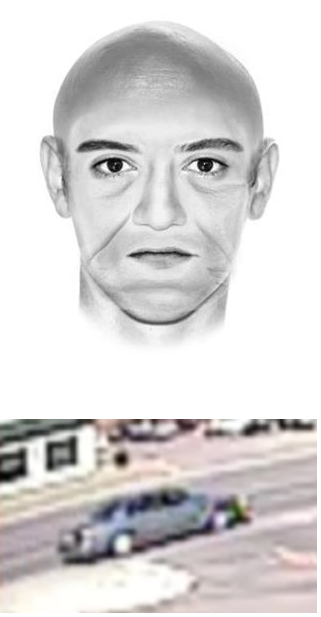

On Sunday, Feb. 19, two male suspects entered a business in the 7500 block of East Evans Avenue while it was closed for the weekend. While the car keys were stolen, both vehicles were not on the property at the time.

Anyone with information about the identification of these suspects is asked to contact Crime Stoppers at 720-913-STOP (7867). You can remain anonymous and may be eligible for a cash reward. You can also call the ACSO Crime Tip Hotline at 720-874-8477 with information.